~ Daniel Thomas Dyer

I probably first came across Keats’ poetry at school, but it wasn’t until my thirties when I was immersed in Sufism that a real appreciation of it began. Picking up Saimma’s schoolgirl copy of some of his poems, I was moved by the beauty of his language as if for the first time. I could now see the mystical insights he was intuiting (and also half-doubting) in the rich, subtle imagery of his poems. At times I wanted to cry out, ‘Yes! Trust your heart!’ as he dramatized that push and pull the heart undergoes with the head, a tussle most of us on this Path will recognise.

When, in the opening line of ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’, Keats writes, ‘Thou still unravished bride of quietness’, I sensed he was addressing not only the urn but his own receptive soul; and when, in ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, he writes, ‘While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad / In such an ecstasy’, I knew he was addressing his own higher self in this nightingale, a self in constant communion with the Divine Beloved. ‘Love is my religion,’ wrote Keats in a letter, and so too is Rumi’s of course. ‘What the imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth,’ he insisted, and I had discovered through Rumi a path devoted to that Divine Beauty he was encountering in his own unique and poignant way. ‘If only he’d had a Rumi at his side, or belonged to some mystical tradition that could make sense of his experiences!’ I remember telling Saimma. Meanwhile, I half-remember some of my mentors on the Sufi path, perhaps Kabir Dede or Jeremy Henzell-Thomas, sharing how they too had perceived an affinity between Keats and Sufism.

All this eventually resulted in an essay I published online for Rumi’s Circle in 2014, called ‘Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” in Light of Rumi’. A reader posted a comment in response to this article not long after it was uploaded:

Thank you so much, Daniel. Today when I read this poem in college for the first time, I knew for sure that it had deeper meanings than what meets the eye. As it is, I’ m growing weary of this material world and as I read the line “Away! Away! For I shall fly away to Thee”, tears filled my eyes and I thought about the day I shall finally dissolve in God and be at blissfull peace at heart. Thank you for your interpretation, it is beautiful.

And then there was a remarkable talk given by another dear mentor, Elizabeth A. Hin, at Keats House, Hampstead, in 2016, called ‘Spiritual Threads and the Weaving of Beauty ~ Sentiments Regarding John Keats and Poetry’. As I listened that evening, it seemed to me that Beth wasn’t just speaking to the small group of us physically present but also to an unseen audience—including Keats himself. That talk took place in the very house where Keats wrote some of his greatest poetry and where he was nursed during the initial stages of his illness and early death.

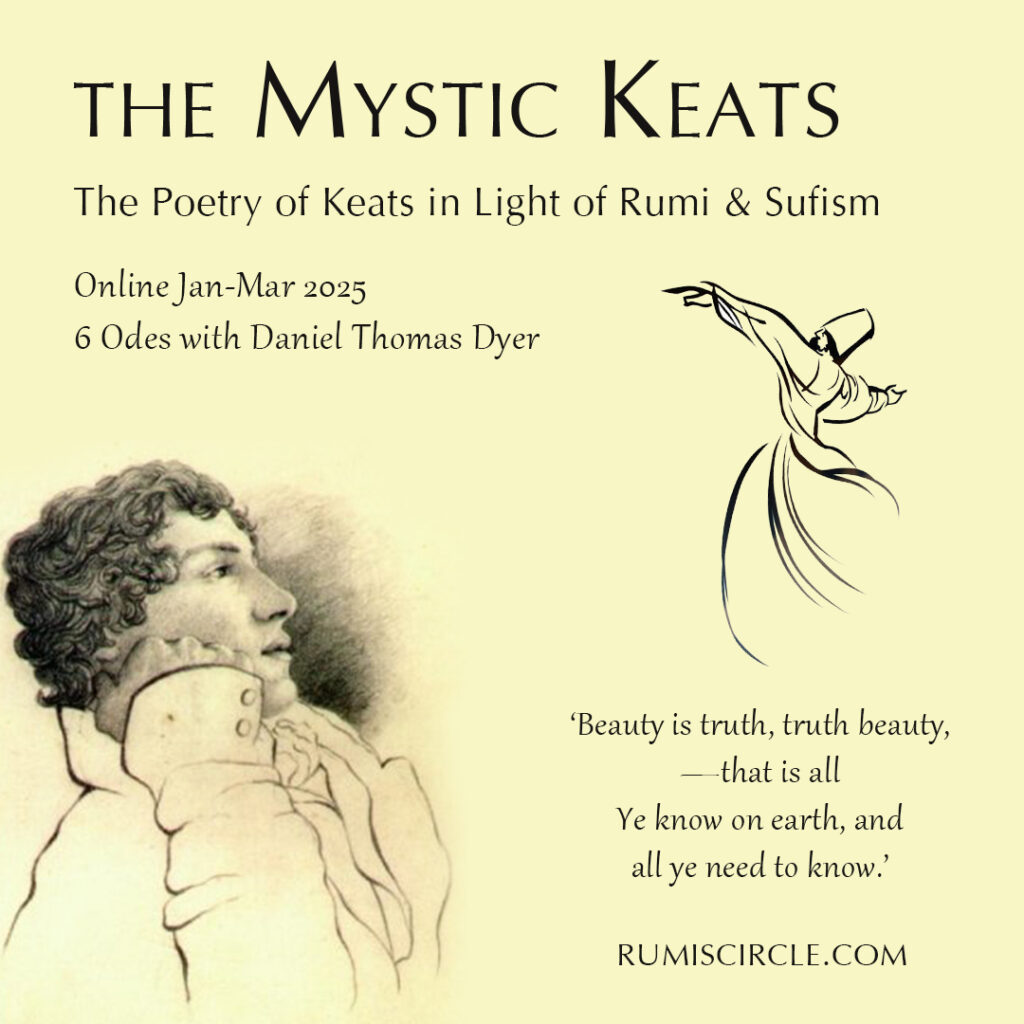

All this has led me on something of an adventure deeper into my own imagination and that of Keats, deeper into the underworld, and deeper into the light. I’ve begun to write a book I’m currently calling The Mystic Keats: Keats in Light of Rumi and Sufism. God willing, I hope to complete it in the next year or two, but as part of the journey I’m also offering a three-month course in 2025 exploring the six famous odes written by Keats in 1819, including ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ and ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’. Viewed through the lens of Sufism, the transcendent realities Keats was intuiting come into deeper, sharper focus, for they are familiar certainties to Mevlana and his lineage—to us here in Threshold.

Put simply, the six celebrated odes that Keats wrote in 1819, two years before his death at the tender age of twenty-five, can help us build a temple in our hearts to receive Spirit. The result is soul. Seen through the lens of Mevlana and the Sufi tradition, this becomes very clear. So I encourage you to build a relationship with Keats—you’ll discover a fellow traveller on this Path with some beautiful insights to share.