Adapted from traditional sources by Kabir Helminski

The Sufis created a system of human development grounded in love and using the power of love to awaken and transform human beings. Rumi taught that it is everyone’s potential to master the art of loving. Love is the answer to the problem of human existence.

The way to God passes through servanthood. The point is to love and be connected with others in that love. The form of Sufi work is typically a group, or spiritual family. The Sufis created a milieu in which human love was so strong that it naturally elevated itself to the level of cosmic love. All forms of love eventually lead to spiritual love. “Ashq olsun,” they say. “May it become love.” They cultivated a kindness and refinement in which love fermented into a fine wine. They encouraged service to humanity as an expression of the love they felt. They accepted a rigorous discipline in order to keep the fire of love burning strongly.

The porter runs to the heavy load and takes it from others,

knowing burdens are the foundation of ease

and bitter things the forerunners of pleasure.

See the porters struggle over the load!

It’s the way of those who see the truth of things.

Paradise is surrounded by what we dislike;

the fires of hell are surrounded by what we desire.

Rumi, Mathnawi II, 1834-7

We are not merely Love’s passive instruments; we are also it’s servants. In order to know how to serve, Love needs to be grounded in knowledge. Love without knowledge is dangerous. With love alone we could burn ourselves and others. With love alone we could be foolish. Love is such an extraordinary and complex power, and the human being has such a great capacity for love. An important part of Sufi education is to acquire a knowledge of love and apply it appropriately.

Adab is courtesy, respect, appropriateness. Adab is not formality; it helps to create the context in which we develop our humanness. Every situation and relationship has its proper adab: between students on the path, in relation to family members and elders, in relation to one’s shaikh. Every level of being also has its adab, including coming into the presence of Truth (Al-Haqq).

The model of adab in the Sufi tradition is the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessing upon him), who said: “None of you will have authentic faith until your hearts are made right, nor will your hearts be made right until your tongues be made right, nor will your tongues be made right until your actions be made right.”

As one begins to become aware of the benefits and possibilities of adab it becomes strikingly clear how much has been lost in contemporary culture in the name of some hypothetical personal freedom and individuality.

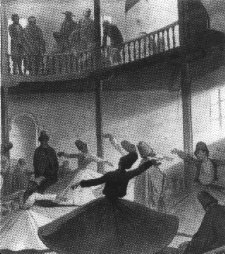

When a dervish steps over the threshold into a Sufi tekkye, he leaves the “world” and its concerns behind. The tekkye is the school of love. We come here to observe, listen, and learn, and to practice service—not to pursue the ambitions of the world, not to satisfy or promote our own egos, nor to consume exciting “spiritual” experiences.

It is vitally important to arrive at the tekkye in a state of ablution—this can consist of taking a shower shortly beforehand. It’s good to have a clean breath and body. One might even consider what one eats before a gathering. If some have the fragrance of musk and roses, while others smell of garlic and onions, the “atmosphere” suffers, so to speak. Wearing modest, clean, and simple clothes is a sign of self-respect. We are coming to a place and occasion of worship—not to a sporting event or a nightclub.

It is important that we arrive at least a little before the actual time of the meeting—ten minutes early is recommended. It is not necessary to give an obligatory hug to everyone you see—especially before the meeting when there may be little time. Once the meeting has begun, our focus is on the process that has begun. Latecomers should find a place to sit if there is room in the circle—but without disturbance of anyone’s meditation. While sitting in a dervish circle during teaching or zhikr, we should be conscious of sitting with dignity. It is considered disrespectful, for instance, if the soles of one’s feet are pointing in the direction of others. At the end of zhikr, we greet the people to our right and left by kissing their hands and giving thanks.

Anyone sponsoring a newcomer to the tekkye should first if possible introduce him or her to the host (meydanji-bashi), who will assist the person further if necessary, and also to the shaikh and his wife.

The life of the tekkye brings us into relationship with people whom we might not choose to be with in the everyday world, and yet slowly we come to understand that every relationship is important and has been provided as an opportunity to know ourselves and purify our hearts. This circle of lovers is learning to manifest the reality of Oneness (tawheed), the reality of brotherhood/sisterhood/spiritual community. We must treat each other not just as family, but even better than most families treat each other. It may be that at the tekkye we learn how to treat our own family as they ought to be treated.

We learn to observe, to control our impulses when that is called for, and to lose our “selves” when that is called for. We learn to behave as if everyone else is of a higher station than ourselves. Our conversation is centered on God and coming into harmony with God and each other. Gossip and backbiting is one of the worst actions any seeker can indulge in—not only the speaking of it, but the listening to it, as well. Backbiting is defined as saying anything behind a person’s back that would displease them (whether it is true or not).

Since we are attempting to bring our selves into alignment with Reality, we will face many tests and it is inevitable that there will be some interpersonal tensions from time to time. Adab helps us to avoid some of the destructive behaviors that could disturb or even destroy relationships in a sufi halka (circle).

A special relationship exists between the dervish and his/her shaikh. The respect and affection that develops results in consideration and attentiveness to the shaikh especially during meetings. The shaikh is the one who sets the tone of the circle and guides the discourse. Ideally, he is like an empty center who responds to the innermost needs of the circle. He perceives the spiritual winds, trims the sails, and sets the course of the boat.

You may not always agree with your shaikh. Take what is useful or meaningful to you and do your best to remember it and integrate it into your life. Take what you do not agree with or do not understand and put it aside where it will not be lost. It may be that one day, far from the dervish circle and your shaikh, you find in it something you really need.

Our possibilities together on this path would be served by increasing our awareness of some simplified aspects of adab:

To be straightforward with sincerity and truthfulness.

To be aware of and have regret for our own faults, rather than finding fault with others.

To be free from the preoccupation, worry, vanity and ambition over the world and the worldly.

To be indifferent to the praise or blame of the general public.

To do what one does for Allah’s sake—not for the desire for reward or the fear of punishment.

To adopt an appropriate humility and invisibility in public and in the meetings of the dervishes.

To serve the good of one’s brothers and sisters with all one’s physical and other resources.

To seek to heal any wound you may have caused to another, and to correct any misunderstanding within three days if possible.

To know that no good will come out of the expression of anger or excessive hilarity.

To be patient with difficulties.

To be indifferent to favor or benefit for oneself, for “receiving one’s due.”

To be free of spiritual envy and ambition, including the desires to lead or teach.

To strive to increase one’s knowledge of Sufism (including Qur’an, hadith, the wisdom of the saints).

To be willing to struggle with one’s ego as much as it prevents one from following proper adab, and to realize that the greatest ally in the transformation of our egoism is Love.

To have a shaikh whom one loves and is loved by, and to cultivate this relationship.

To accept suggestions and even criticism from one’s shaikh with gratitude and non-defensiveness. (The proper response is always “Eyvallah”—”All good comes from God.”)

To keep no secrets from one’s shaikh.

To ignore any extraordinary states that occur during one’s worship or practice.

To consult one’s shaikh over major decisions in life, especially journeys.

To do neither less nor more than the practices suggested by one’s shaikh (although to ask for more is always permitted).

To seek instead to make one’s practices more and more inwardly sincere, rather than outwardly apparent.

To realize that one’s shaikh is a human being with his own limitations; in his or her role as shaikh, he (or she) has some states that are inspired and some states that are not. Yet if there is enough love between dervish and shaikh the limitations of personality will be gracefully overcome.

Threshold Society, Revised August 2006